20220419

Thursday, January 26, 2022

Looking back, I spent most of last year writing a medium-length novel titled Celebration. The work was inspired by Diaspora artist Fiona Tan’s Ellipsis, which I began to write. For the epiglogue, I quoted the following words of Tan.

I think of what I will remember thirty years from now; I remember what I will think of thirty years from now.

If you don’t remember, you can’t conceive of it.

It comes to mind because you remember it. Or perhaps when it comes to mind, we remember that we have not forgotten it.

Fiona Tan has a video piece titled May You Live In Interesting Times (unfortunately I have not seen it yet).

Interesting generation.

Interesting times.

It would be very interesting if someday I would remember something that I once thought, but that I have completely forgotten.

Perhaps I am living in more interesting generation than I think I am now.

Now, this is the third research for the “Scenes of New Habitations” project.

When I visited the Tokyo Air City Terminal at the end of last year, I was convinced of my own fierce resistance to the “bad nostalgia” that “only sugarcoats and beautifies the past” (Shuhei Hosokawa). I suppose this is mixed with my contempt for those who visit tourist attractions advertised with catchphrases such as “nostalgic in spite of being new,” “nostalgic,” and “good old Japan,” and happily consume “products” marketed as “nostalgic scenery.”

In this respect, the Tokyo Air City Terminal, a limousine bus depot, was a modest and colorless “product” as a “transit point” for travelers coming and going from the airport. And it was at this place, where you can only “can get on and off, can get through, can get past,” that Keitany’s melody with the word “can” was born, and that song led me to write the text Hakozaki as well.

At the end of an interesting day at Hakozaki, we had almost intuitively decided that our next destination would be the Foreign Cemetery in Yokohama, and that too in Motomachi.

Come to think of it, ever since I was in my early twenties, I have been asking myself, which is your home country? and where is your hometown? Whenever I encountered such questions, I was made aware of my own circumstances that led me to ask such questions. That is why I was sometimes moved to tears by the voice of Hiroto Komoto, who sang spontaneously, “The place where I died hanging down is my real hometown.” I wondered if it was okay to call the place where I died, not the place where I was born, my hometown. The title of the song, Navigator, also resonated with my “soul” in my mid-twenties, when I was even more nervous and in need of help. Hiroto Komoto’s voice was actually religious. His voice encouraged me. The navigator is the soul. I thought then, and I still think now, that if I follow my soul, I will be honest.

Of course, dying is extreme.

We don’t know what the future holds. I don’t want to imagine dying at all. But I am wondering if such a way of thinking is possible (The Yellow Monkey’s JAM, which I listened to at the exact same time, was also suggestive. One of the lyrics reads, “No Japanese among the passengers.” Even if I had been on that plane, the lyrics of that song would still be the same.)

I don’t think about dying that often. Rather, I think only about how I should survive.

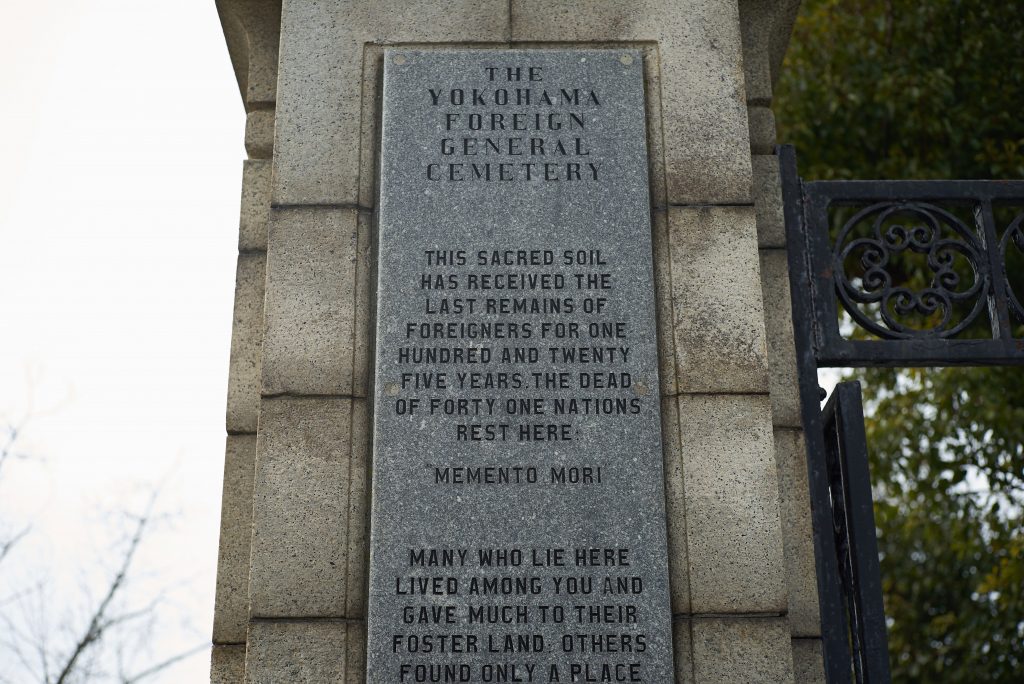

In Motomachi in the middle of winter, I climbed the gentle slope lined with elegant apartments to reach the entrance to the foreigner’s cemetery and found the words “memento mori” mixed in with the English information. Looking at this phrase, I couldn’t help but wonder about the homelands of the “foreigners” who came to faraway Japan in Perry’s time (the end of Edo period) and died abroad. At the same time, the homelands of the Japanese abroad who have died far away from Japan, far away from the sea.

It may sound peculiar if you think of it as crossing a country.

However, even here in Japan, it is rare for a person to live out his or her life peacefully in the land of his or her birth. If we look ahead to the next 100 years, it may not be unusual for Japanese people to be forced to “emigrate” to other countries for a variety of reasons. No, I don’t know. But I would like to imagine it.

In 1986, when the Foreign Cemetery became open to the public, a tin toy store and a Christmas Toys also opened at the top of the hill in Motomachi. A fairytale-like house with an aged Santa Claus doll welcomes visitors. On the entrance door, “333 days to go until Christmas” is painted in chalk, and I feel a selfish sense of good fortune at the triples. Even if it is 355 days before Christmas, you can still enjoy Christmas here. As I was lost in the company of overpriced antique toys, such as Elge’s Tintin doll and a tin reindeer reminiscent of the heart-thirsty man in the Wizard of Oz, I imagined that if I had been brought here as a child, I would have really felt like I had wandered into a dream.

How sweetly sinful it is that there is such a store tickling our unconscious that yearns for their faraway lands, right next to a cemetery where those who “died abroad” in Japan are buried.

It was by chance that I learned of the existence of this “tower.” Late last year, while writing a novel and researching the “Oriental Pearl,” a radio tower in Shanghai, I came across a stranger’s blog, where he had posted a photo of the “Yokohama Port Symbol Tower” looking up from a spacious lawn. I was somehow attracted to the lawn, the blue sky, and the rather charming, lean white tower.

On the way to the tower, there were two masonry objects standing in the corner of a container yard facing the sea. I finally found out that they were flower beds when I saw a monument inscribed with the words, “Faraway Things – Yokohama ‘Flower Bed’”. The flowers in the flower bed were wilting. Was it inevitable because it was winter?

After that, we spent about 30 minutes walking across the lawn, which I had wanted to step on, and finally reached the foot of the “tower.”

At the entrance, there is a cast stainless steel sculpture in the shape of a shell, measuring 6 meters both vertically and horizontally and weighing 15 tons. Apparently, this sculpture is a counterpart to the flower bed mentioned earlier. According to the information, the sculpture was created in 1985. The artist’s name is also clearly inscribed. We were just children when this work was created. The years have passed, and we, who are now in our forties, are laughing at the funny, somewhat ostentatious sound of “Harukanaru.” We couldn’t find anything that looked like an elevator, so we climbed the spiral staircase in the tower, about 50 meters, and by the time I reached the observation deck, I was out of breath (tough luck for Keitany, who had to do the same with his guitar). The sky was clear and brilliant, the sea was dazzling blue, the boats and the city were clearly visible, and it was a great vantage point. The free telescope and the chairs, which I imagine have been there for about 35 years when it first opened, were tasteful.

After descending from the tower, I filmed Hakozaki performance and reading in a mostly deserted corridor against the backdrop of a clear blue sky. Keitany’s voice softly sings, “The sun shines,” and his voice softly touches my heart.

Interesting generation.

Interesting times.

I wanted to continue to live such a time as this, surrounded by the sinking white light, where we could overlap our thoughts about living and surviving.